Table of Contents

The Life and Music of Paul Hindemith: Master Craftsman of 20th Century Classical Music

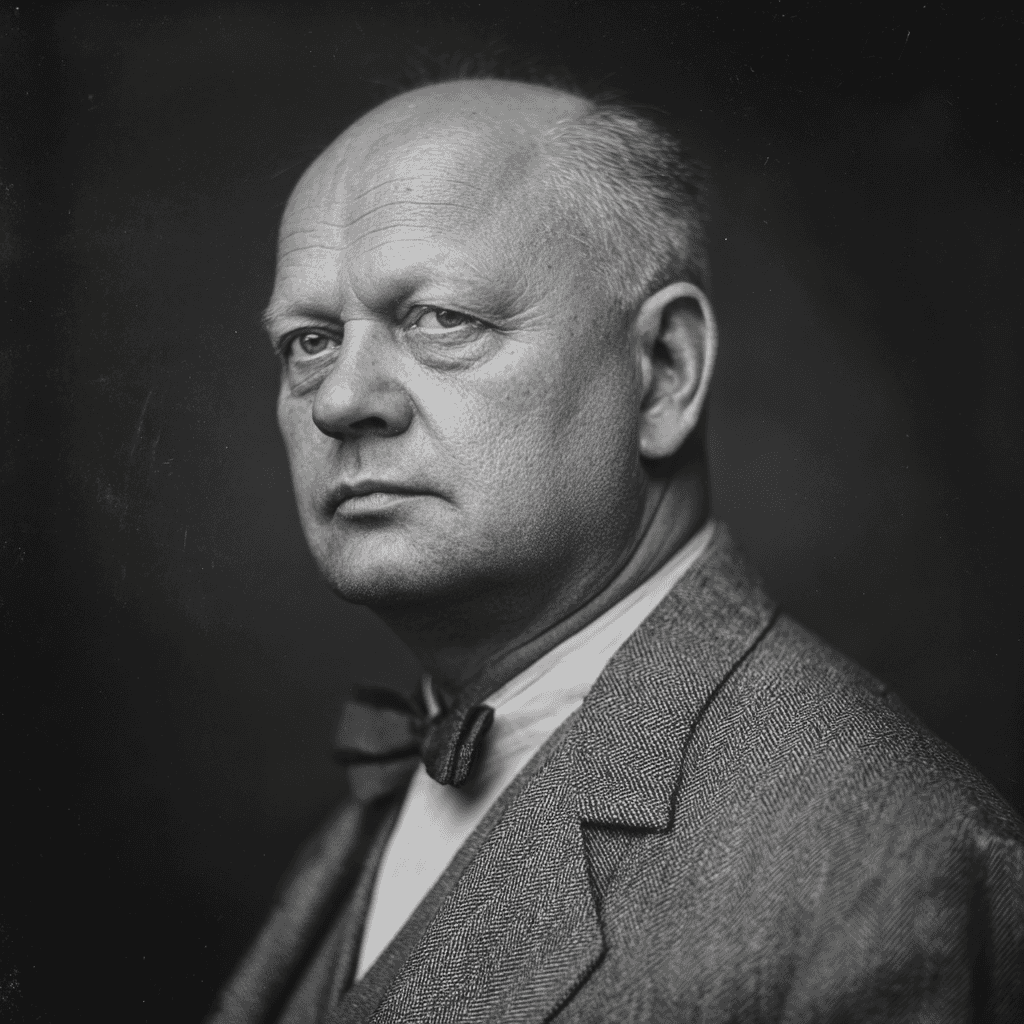

Paul Hindemith (1895-1963) stands as one of the most prolific and influential composers of the 20th century, yet his name often remains overshadowed by contemporaries like Stravinsky, Schoenberg, or Bartók. This oversight does a disservice to a composer whose practical philosophy, masterful craftsmanship, and extensive catalog shaped modern classical music in fundamental ways. From his revolutionary concept of Gebrauchsmusik to his comprehensive theoretical writings, Hindemith created a musical legacy that continues to influence composers, performers, and educators worldwide.

Unlike many modernist composers who pursued increasingly abstract and experimental paths, Hindemith charted a unique course that balanced innovation with accessibility, tradition with progress. His music speaks with a distinctive voice that is simultaneously modern and timeless, intellectual yet deeply human. This comprehensive exploration examines Hindemith’s remarkable journey from a working-class German violinist to an international musical figure, his evolution as a composer through political upheaval and exile, and the enduring impact of his musical philosophy.

Whether you’re a classical music enthusiast discovering Hindemith for the first time, a performer exploring his extensive repertoire, or a student studying 20th-century music history, understanding Hindemith’s life and work provides essential insights into how classical music navigated the turbulent waters of modernism while maintaining its connection to broader audiences.

Early Life and Musical Formation (1895-1920)

Childhood and Family Background

Paul Hindemith was born on November 16, 1895, in Hanau, near Frankfurt, Germany, into a working-class family with no significant musical background. His father, Robert Rudolf Hindemith, was a house painter and decorator who later became involved in the family’s musical activities as a somewhat tyrannical manager. His mother, Marie Sophie Warnecke Hindemith, came from a family of farmers and servants.

The Hindemith household was marked by financial struggle and domestic tension, factors that would profoundly influence Paul’s practical approach to music-making. Despite these challenges, or perhaps because of them, music became the family’s path to economic survival. Robert Hindemith, recognizing potential profit in his children’s musical abilities, pushed them relentlessly toward professional performance.

Early Musical Training

Paul’s musical education began at age seven when his father arranged violin lessons. By age eleven, he was studying at the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt, one of Germany’s most prestigious musical institutions. His teachers included Adolf Rebner (violin), Arnold Mendelssohn (composition), and Bernhard Sekles (composition and counterpoint).

At the conservatory, Hindemith demonstrated exceptional abilities not just as a violinist but as a comprehensive musician:

- Multi-instrumentalist: Mastered violin, viola, piano, and numerous other instruments

- Sight-reading prowess: Could play complex scores at sight

- Compositional facility: Began writing substantial works while still a student

- Ensemble skills: Excelled in chamber music and orchestral playing

Professional Beginnings

By 1914, at just nineteen, Hindemith was appointed concertmaster of the Frankfurt Opera Orchestra, a remarkable achievement that provided financial stability and professional experience. This position exposed him to the entire operatic repertoire and the practical demands of professional music-making.

During World War I, Hindemith served in the German army from 1917 to 1918, though he was stationed relatively safely in Alsace playing in a regimental band rather than in combat. Even during military service, he continued composing, including his First String Quartet, Op. 10, which showed early signs of his distinctive voice.

The Revolutionary Years: Weimar Republic and Rise to Prominence (1920-1933)

Breaking with Tradition

The 1920s saw Hindemith emerge as a leading figure in German musical modernism. The post-war Weimar Republic created an atmosphere of artistic experimentation and cultural revolution that perfectly suited his innovative temperament. During this period, Hindemith’s music underwent rapid evolution:

Early Expressionist Phase (1919-1923):

- Influenced by Schoenberg and expressionism

- Works like the One-Act Operas showed provocative, even scandalous themes

- Suite “1922” for piano incorporated jazz elements

- Aggressive dissonances and angular melodies dominated

Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) Period (1923-1927):

- Rejection of romantic excess and expressionist emotionalism

- Clear, linear writing with emphasis on counterpoint

- Kammermusik series (1921-1927) exemplified this aesthetic

- Music became more accessible while remaining modern

The Amar-Hindemith Quartet

In 1921, Hindemith founded the Amar-Hindemith Quartet with Turkish violinist Licco Amar. As the ensemble’s violist, Hindemith championed both contemporary music and neglected early music, particularly Baroque works. The quartet’s activities profoundly influenced his compositional development:

- Performance experience shaped his practical approach to writing

- Repertoire study deepened his understanding of musical history

- International touring expanded his cultural horizons

- Advocacy for new music established him as a modernist leader

Theoretical Development and Gebrauchsmusik

During the mid-1920s, Hindemith developed his concept of Gebrauchsmusik (utility music or music for use), a philosophy that would define much of his career. This approach rejected the romantic notion of art for art’s sake, instead emphasizing:

Practical Accessibility:

- Music written for amateur and student performers

- Technical demands matched to intended performers

- Clear, playable parts without unnecessary difficulty

- Educational value alongside artistic merit

Social Function:

- Music as community activity rather than passive consumption

- Compositions for specific occasions and purposes

- Breaking down barriers between “high” and “low” art

- Democratic approach to music-making

Notable Gebrauchsmusik works include:

- Spielmusik (Music for Playing) series

- Schulwerk für Instrumental-Zusammenspiel (School Work for Instrumental Ensemble)

- Plöner Musiktag (Music for a Day in Plön)

- Various pieces for youth orchestras and amateur groups

Major Works of the Weimar Period

The late 1920s and early 1930s saw Hindemith produce some of his most significant works:

Cardillac (1926): His first full-length opera, based on E.T.A. Hoffmann’s story, established him as a major operatic composer. The work’s neo-classical clarity and dramatic power marked a new direction in German opera.

Neues vom Tage (1929): A satirical opera featuring modern themes including divorce and journalism, it scandalized audiences with a scene featuring a soprano singing in a bathtub.

Concert Music for Strings and Brass (1930): This work became a staple of the orchestral repertoire, demonstrating Hindemith’s mastery of instrumental color and formal structure.

Conflict with the Nazi Regime and Exile (1933-1940)

The Political Climate

Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 dramatically altered Germany’s cultural landscape. Hindemith initially believed he could navigate the new regime while maintaining his artistic integrity, but this proved increasingly impossible. Several factors made him a target:

Musical Modernism: Though less radical than Schoenberg, Hindemith’s music was still considered “degenerate” Professional Associations: Collaborated with Jewish musicians and leftist artists Moral “Degeneracy”: His operas contained themes the Nazis found objectionable International Connections: Extensive foreign contacts made him suspect

The Mathis der Maler Crisis

The composition and premiere of Mathis der Maler (Matthias the Painter) became the focal point of Hindemith’s conflict with the Nazi regime. The opera, based on the life of Renaissance painter Matthias Grünewald, explored the artist’s role during political upheaval – a barely veiled commentary on contemporary Germany.

The Symphony “Mathis der Maler” (1934): Extracted from the opera before its stage premiere, the symphony was conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler with the Berlin Philharmonic. Its success temporarily protected Hindemith, with Furtwängler publicly defending him in the article “The Hindemith Case.”

The Opera’s Suppression: Despite the symphony’s success, the opera itself was banned from German stages. The work’s themes of artistic conscience versus political pressure were too provocative for the regime. The opera wouldn’t premiere until 1938 in Zürich, after Hindemith had left Germany.

Forced Emigration

By 1937, Hindemith’s position in Germany had become untenable:

- His music was banned from public performance

- He was forced to resign from the Berlin Hochschule

- His wife Gertrud, partly Jewish, faced increasing danger

- Professional opportunities disappeared

The couple initially moved to Switzerland in 1938, where Hindemith had teaching opportunities. But with war approaching, they looked further afield for permanent refuge.

American Years and International Recognition (1940-1953)

Establishing a New Life

In February 1940, Hindemith arrived in the United States, joining the wave of European artists and intellectuals fleeing fascism. Yale University appointed him to their music faculty, where he would remain until 1953. The transition wasn’t easy:

Cultural Adjustment:

- Language barriers despite good English

- Different academic traditions

- Homesickness for European culture

- Adaptation to American musical life

Professional Rebuilding:

- Establishing reputation with new audiences

- Building relationships with American musicians

- Navigating different performance traditions

- Creating new works for American ensembles

Teaching at Yale

At Yale, Hindemith became one of America’s most influential composition teachers. His pedagogical approach emphasized:

Comprehensive Musicianship:

- Students must understand all aspects of music

- Practical skills alongside theoretical knowledge

- Historical awareness and stylistic versatility

- Emphasis on craftsmanship over inspiration

Notable Students included:

- Lukas Foss

- Norman Dello Joio

- Mel Powell

- Harold Shapero

- Many who shaped American music education

Major American Works

The American period saw Hindemith create some of his most enduring compositions:

Symphonic Metamorphosis of Themes by Carl Maria von Weber (1943): This brilliant orchestral showpiece, based on Weber’s piano duets, became Hindemith’s most popular orchestral work. Its colorful orchestration and rhythmic vitality appealed to American audiences while maintaining his sophisticated craftsmanship.

Ludus Tonalis (1942): Subtitled “Studies in Counterpoint, Tonal Organization, and Piano Playing,” this monumental piano cycle represents Hindemith’s theoretical and compositional philosophy in musical form. Often compared to Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, it consists of:

- Twelve fugues in different keys

- Eleven interludes connecting the fugues

- Prelude and Postlude (the Postlude is the Prelude inverted and retrograde)

Symphony “Die Harmonie der Welt” (1951): Another symphony derived from an opera, this work explores cosmic harmony through the story of astronomer Johannes Kepler. It represents Hindemith’s mature philosophical and musical thinking.

Theoretical Writings

During his American years, Hindemith codified his musical philosophy in several important texts:

The Craft of Musical Composition (1937-1939): This two-volume work outlined his theoretical system, including:

- Series 1 and 2: Hierarchical arrangement of intervals and chords

- Melodic and harmonic analysis methods

- Practical composition techniques

- Alternative to Schoenberg’s twelve-tone system

A Composer’s World (1952): Based on his Harvard lectures, this book explored broader philosophical questions about music’s role in society, the creative process, and musical meaning.

Return to Europe and Late Period (1953-1963)

The Swiss Years

In 1953, Hindemith returned to Europe, settling in Switzerland. He accepted a position at the University of Zürich while maintaining an international conducting career. This decision reflected several factors:

- Nostalgia for European culture

- Desire for different creative environment

- Switzerland’s neutrality and stability

- Proximity to German-speaking world without political complications

Late Compositional Style

Hindemith’s late works showed increasing introspection and refinement:

Characteristics of the Late Style:

- Greater harmonic warmth

- More lyrical melodic writing

- Nostalgic references to earlier styles

- Philosophical and spiritual themes

- Masterful synthesis of his various influences

Significant Late Works:

- Pittsburgh Symphony (1958)

- Die Harmonie der Welt opera (1957)

- Mass for Mixed Chorus (1963)

- Organ Concerto (1962)

Conducting Career

Hindemith increasingly appeared as conductor of his own works and other repertoire. His interpretations emphasized:

- Structural clarity

- Rhythmic precision

- Balanced textures

- Objective rather than romantic approach

He conducted major orchestras worldwide, including the Vienna Philharmonic, Berlin Philharmonic, and New York Philharmonic, helping establish authentic performance traditions for his works.

Musical Style and Compositional Techniques

Harmonic Language

Hindemith’s harmonic system, while complex, maintained connection to tonality:

Expanded Tonality: Unlike Schoenberg’s atonality, Hindemith believed in tonal centers, though vastly expanded from traditional practice. His Series 1 ranked intervals by decreasing stability:

- Octave

- Fifth

- Fourth

- Major third

- Minor sixth

- Minor third

- Major second

- Minor seventh

- Major second

- Minor seventh

- Augmented fourth/Diminished fifth

Chord Classification: Series 2 organized chords by harmonic tension, from consonant triads to complex dissonances. This system allowed logical harmonic progression without traditional functional harmony.

Contrapuntal Mastery

Hindemith’s counterpoint represents perhaps his greatest technical achievement:

Linear Independence: Each voice maintains melodic integrity Rhythmic Variety: Different rhythmic patterns create complex textures Motivic Development: Small musical ideas generate entire movements Neo-Baroque Techniques: Updated fugue, canon, and invention forms

Formal Innovation

While respecting classical forms, Hindemith adapted them for modern expression:

Sonata Form Modifications:

- Altered key relationships

- Continuous development rather than distinct sections

- Thematic transformation techniques

- Synthesis rather than recapitulation

Variation Techniques:

- Melodic variation

- Harmonic reinterpretation

- Rhythmic transformation

- Character variations

Complete Catalog Overview

Orchestral Works

Hindemith’s orchestral output includes:

- Seven Symphonies including “Mathis der Maler” and “Die Harmonie der Welt”

- Numerous Concertos for virtually every orchestral instrument

- Symphonic Metamorphosis and other Weber arrangements

- Der Schwanendreher for viola and orchestra

- Trauermusik for viola and strings (written for King George V’s funeral)

Chamber Music

The chamber music catalog is vast and varied:

- Seven String Quartets

- Sonatas for every orchestral instrument with piano

- Kammermusik series (seven works for various solo instruments and chamber orchestra)

- Wind quintets and brass ensemble works

- Kleine Kammermusik for wind quintet

Opera and Vocal Works

Beyond his famous operas, Hindemith wrote:

- Nine Operas including Cardillac, Mathis der Maler, Die Harmonie der Welt

- Das Marienleben (The Life of Mary) song cycle

- When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d (Whitman requiem)

- Numerous choral works both sacred and secular

- Six Chansons and other vocal ensemble pieces

Educational Works

Hindemith’s commitment to music education produced:

- Études for various instruments

- Elementary Training for Musicians

- Traditional Harmony textbooks

- Sing- und Spielmusiken for amateur groups

Performance Practice and Interpretation

Approaching Hindemith’s Music

Performers face unique challenges and opportunities in Hindemith’s music:

Technical Demands:

- Clean articulation essential

- Rhythmic precision crucial

- Balance between voices

- Understanding harmonic progressions

Interpretive Considerations:

- Avoid romantic excess

- Maintain linear clarity

- Respect tempo markings

- Balance emotion with structure

Recording Legacy

Notable recordings have established performance traditions:

Historic Recordings:

- Hindemith’s own conducting

- Early advocates like William Primrose

- Deutsche Grammophon complete edition

- Contemporary performance practice recordings

Influence and Legacy of Paul Hindemith

Impact on Music Education

Hindemith’s educational philosophy transformed music teaching:

Comprehensive Musicianship Movement: His integrated approach influenced curriculum development worldwide

Practical Application: Emphasis on making music rather than just studying about it

Democratic Access: Music education for all ability levels

Compositional Influence

Subsequent composers showing Hindemith’s influence include:

- American School: Students and followers in the US

- German Tradition: Post-war German composers

- Film Music: His orchestration techniques widely adopted

- Wind Band Literature: Major influence on serious wind ensemble composition

Contemporary Relevance

Hindemith’s music and philosophy remain relevant because:

Practical Wisdom: His emphasis on craft and communication resonates in our digital age

Educational Value: His pedagogical works still used worldwide

Performance Opportunities: Extensive catalog provides repertoire for all levels

Theoretical Alternative: His tonal system offers alternative to both traditional harmony and atonality

Critical Reception and Reassessment

Contemporary Reception

During his lifetime, Hindemith faced varied critical response:

1920s-30s: Hailed as leading modernist Nazi Era: Condemned as degenerate American Period: Respected but considered conservative Late Period: Seen as out of step with avant-garde

Posthumous Reevaluation

Since his death, Hindemith’s reputation has undergone significant reassessment:

1960s-70s: Temporary eclipse by avant-garde 1980s-90s: Gradual revival and appreciation 21st Century: Recognition as major 20th-century figure Current Status: Secure place in repertoire and education

Conclusion: Hindemith’s Enduring Significance

Paul Hindemith’s life and music embody the struggles and triumphs of 20th-century classical music. His journey from working-class German violinist to international musical figure parallels classical music’s own transformation from elite art form to more democratic cultural expression. Through political upheaval, exile, and changing aesthetic fashions, he maintained his commitment to craftsmanship, practicality, and musical communication.

His greatest achievement may be proving that modernism and accessibility need not be mutually exclusive. While contemporaries pursued increasingly esoteric paths, Hindemith demonstrated that contemporary music could speak to broader audiences without sacrificing sophistication or innovation. His extensive catalog ensures that performers at every level, from student to professional, can find rewarding challenges in his music.

The concept of Gebrauchsmusik remains remarkably relevant in our current age, where questions about art’s social function and accessibility continue to generate debate. Hindemith’s vision of music as practical activity rather than passive consumption anticipates contemporary concerns about cultural participation and community engagement.

For performers, Hindemith offers a lifetime of exploration across every genre and instrument. For educators, his pedagogical works and philosophy provide proven methods for comprehensive musical training. For composers, his theoretical writings and compositional example offer alternatives to both traditional and avant-garde approaches. And for listeners, his music provides that rare combination of intellectual stimulation and emotional satisfaction.

As we continue to grapple with classical music’s role in contemporary society, Hindemith’s example becomes increasingly valuable. He showed that tradition and innovation, craftsmanship and creativity, accessibility and sophistication could coexist productively. His music doesn’t merely survive as historical artifact but continues to live through performance, study, and influence.

Paul Hindemith’s legacy reminds us that great art serves human needs – for beauty, meaning, community, and expression. In pursuing these goals with integrity, skill, and dedication, he created a body of work that transcends its historical moment to speak to universal human experiences. This, ultimately, is why Hindemith’s music endures: not because it was revolutionary or traditional, German or American, modern or classical, but because it is profoundly, generously, and authentically musical.